|

|

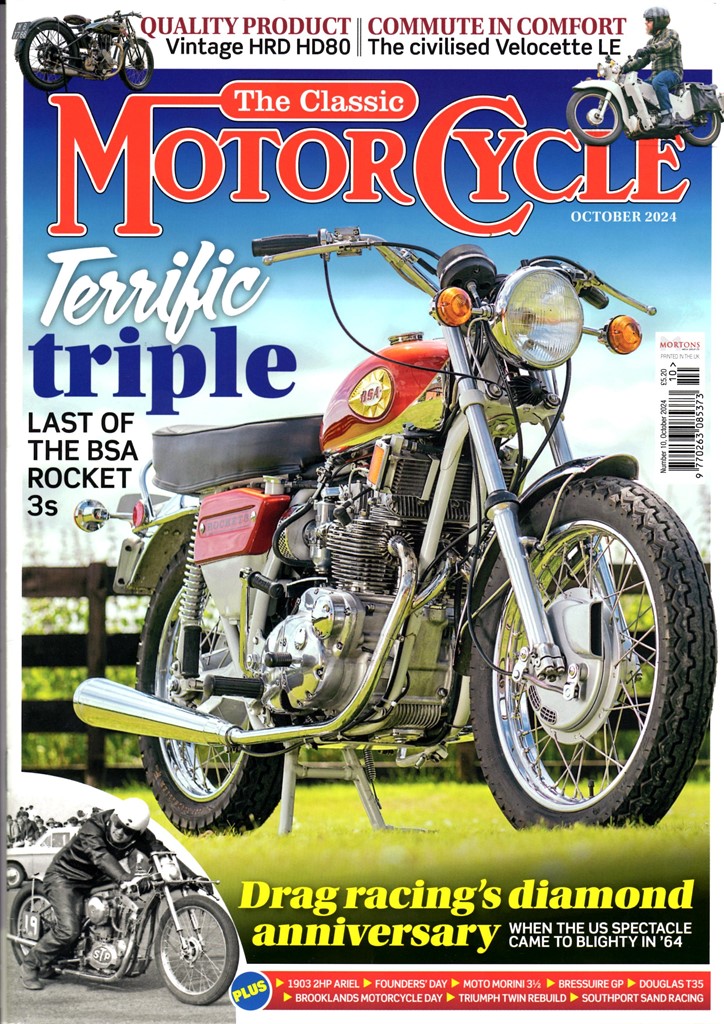

Side by side with the Americans

The 1964 British International Drag Festival was the first of its kind,

an event which was to introduce a new motorsport to the UK.

Words: ALAN TURNER Photographs: MORTONS ARCHIVE

A full six decades have passed since a new motorsport discipline landed on UK shores, announcing its arrival with an all-out assault on the senses. The occasion was the 1964 British International Drag Festival.

This pioneering event, soon known as ‘Dragfest,’ was the brainchild of Sydney Allard. It proved to be so influential in generating interest in this new discipline that within a couple of years Santa Pod in Northamptonshire became Europe’s first permanent dragstrip. For some context of the sea-change in motorsport this represented, we are fortunate in having some recall provided by Dave Lecoq, who was not only there, but took part in the event. Speaking to Dave recently, his recollections come with the caveat that this was something that happened a long time ago...!

|

|

Drag racing started in postwar USA. It began as authorities needed a solution to the increasing popularity of illegal street racing in California. From there, it spread rapidly and soon there were tracks, racers and a multitude of people involved across the States. ‘Hot Rod’ magazine, the sport’s bible, helped spread the word.

In the UK, straight-line sport at the time was confined to sprinting. Many of the airfields hurriedly built for the Second World War still existed. Most had been preserved on a ‘care and maintenance’ basis but were fast returning to private ownership. Hence, many were accessible, could be hired cheaply and still offered a good surface. While competitors often raced side-by-side, the competitive element was almost always dependent on the clock’s verdict.

|

|

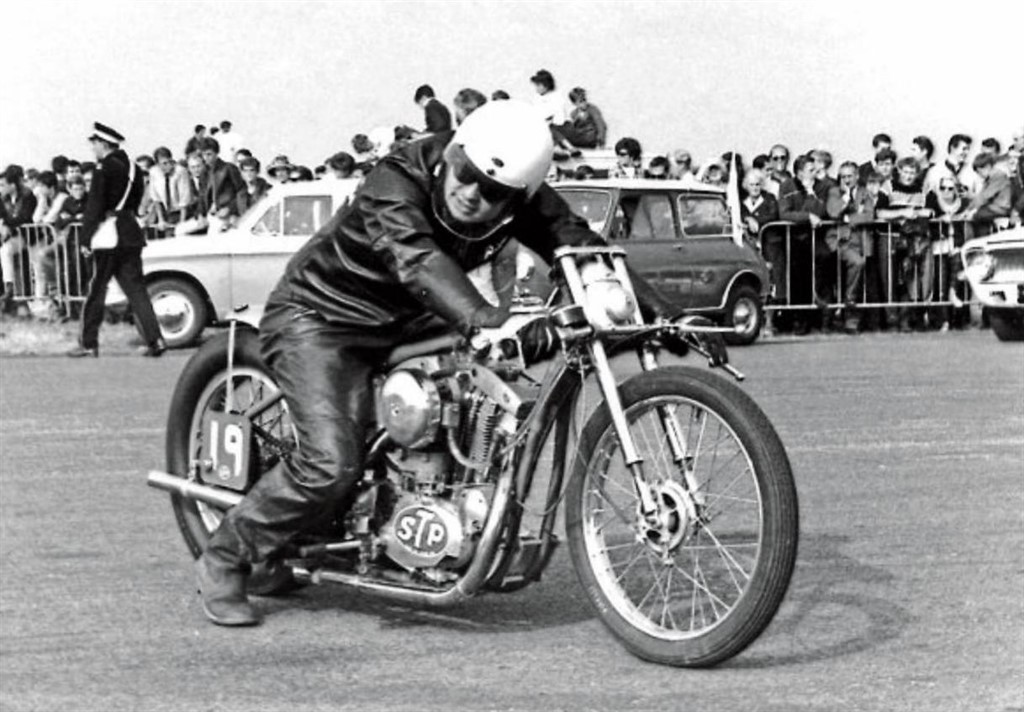

Dave Lecoq was a fairly typical bike sprinter. He had a good job in engineering, useful when it came to modifying machines as well as providing the funds to travel and compete in meetings around the country. Sprinting was a hobby that offered adventure. Far from home, overnight accommodation might be a tent, the back of a van, sometimes just under the stars. As everyone was trying to go quicker, this simple common goal created a camaraderie that was equally important. If the timed runs had all been taken at a sprint, and enough riders had fuel and inclination, there would be a knockout competition, run tournament-style, so essentially–drag racing! This was rarely the main purpose of the day.

When news of the forthcoming British International Drag Festival broke, it became a source of much wonder. Knowledge of the USA was scant and usually gleaned via magazines, newspapers and either of the two TV channels available. Few people had personal experience of the States. Undeniably clear was drag racing had taken the essence of sprinting and turned it into a professional sport with organised teams turning out beautifully prepared machinery, capable of spectacular performances.

|

|

As this country’s driving force behind the forthcoming event, who was Sydney Allard? Born in 1910, he was soon steeped in motor sport. Before he was 20, he became a member of the Streatham & District Motorcycle Club and raced a Morgan at Brooklands. This was the start of a long and successful competition career including trials, rallying and hill-climbing (he was 1949 British Champion), even the Le Mans 24 Hours. His family business was Adlards (note spelling), a large south London Ford car dealership. Under his own Allard name, he was also the manufacturer of sports cars, most powered by V-eight engines. He took victory in the 1952 Monte Carlo Rally in one of his eponymous cars.

By the late 1950s, the wider world of economics was making small-scale car manufacture non-viable, so the Allard company’s focus changed to tuning and sporting accessories, the go-faster goodies. An indulgence was to create Britain’s first dragster, a four-wheeler dedicated to covering the quarter mile of a typical dragstrip in the quickest possible time. One of Hot Rod magazine’s regular advertisers was Moon Equipment, run by the entrepreneurial Californian Dean Moon whose imagination created ‘must-have’ stylish customising parts for hot rodders. Those ubiquitous ‘moon eyes’ were his company cartoon logo and were soon well known to anyone watching British road-racing in the 1960s as John Cooper had appropriated the design for his helmet.

The development of the Allard dragster project had been closely followed, and regularly reported on, by Denis ‘Jenks’ Jenkinson, well known Motor Sport magazine correspondent. As a UK first, the Allard Dragster brought international attention and when the mercurial American drag racer Dante Duce read of it, he got in touch with Sydney Allard. He proposed a transatlantic challenge. Dean Moon, who had supplied Allard with parts for his project, had sold his ‘Mooneyes’ dragster by then, but managed to negotiate its return. Shipment to the UK was arranged to compete against the Allard creation. As a result, a brief series of match races took place in 1963. This was for the SEMA Trophy. SEMA (Speed Equipment Manufacturers’ Association), an American organisation, offered the award to encourage drag racing in the UK. An initial outing at Silverstone included the Allard and a couple more pioneering British-built dragsters, as well as top motorcycle sprinter George Brown. The dragsters appeared later at Brighton for the Speed Trials, an event that regularly attracted huge crowds. They were joined by the Harvey Aluminium Special, a dragster owned by Mickey Thompson, another of the West Coast hot rod and drag race fraternity who organised his trip to the UK on his own initiative.

|

|

Word spread of this drag racing spectacle. Sydney Allard sought to capitalise on this sudden interest. Could he get enough American drag racers to come to this country and put on a suitable display? On the other side of the Atlantic, Wally Parks, founding editor of Hot Rod magazine and now head of the National Hot Rod Association (NHRA), became the main man. Dante Duce had been persuasive with his account of the reception the Americans had received in the SEMA series. Parks was keen to expand drag racing, and the United Kingdom and the Allard connection looked to be a good opportunity.

This was the early 1960s and crossing the Atlantic was a very expensive business. An ordinary passenger sea crossing was around £180 (roughly £1800 at today’s values), yet even that was still only about a third of the air fare. However, another of Sydney Allard’s talents was making things happen. The embryo organisation became the British Drag Racing Association, 10 people with experience in organising race events. Gerry Belton, his Allard company man, became the main contact while many of the organising team were drawn from the suitably qualified ranks of National Sprint Association officials. Parks was even more industrious in America, as he organised racers and secured sufficient budget. It was a major challenge, financially and logistically, but he managed it.

|

|

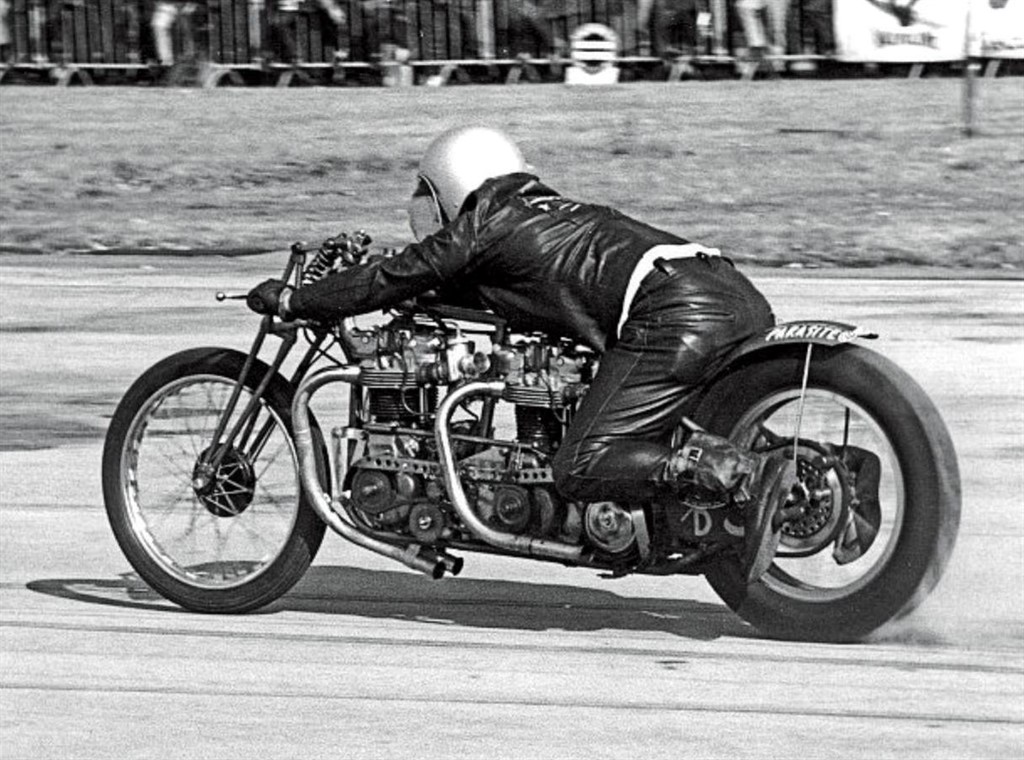

The American team was eventually finalised as 11 four-wheel drag racers and just two motorcycles: Don Hyland on ‘Parasite’, a double-engined Triumph, and Bill Wood on ‘Iron Horse’, a Harley-Davidson V-twin. They would all come over by sea following the end of the American drag race season. The competition was to take place over six one-day meetings, held over three consecutive weekends at venues around the country.

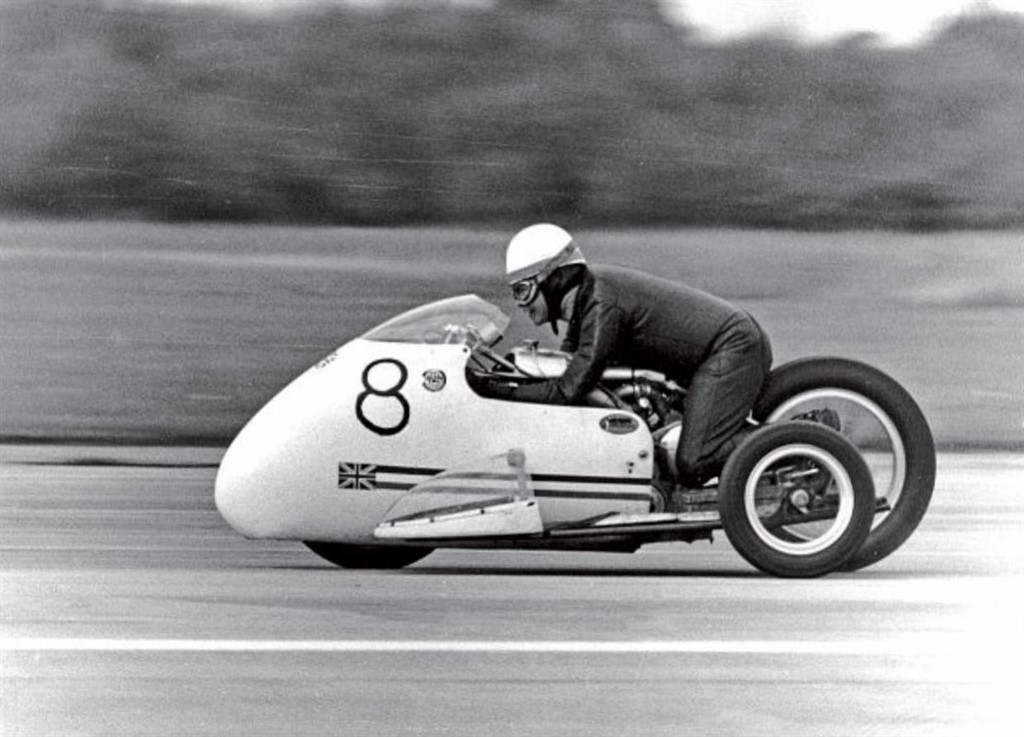

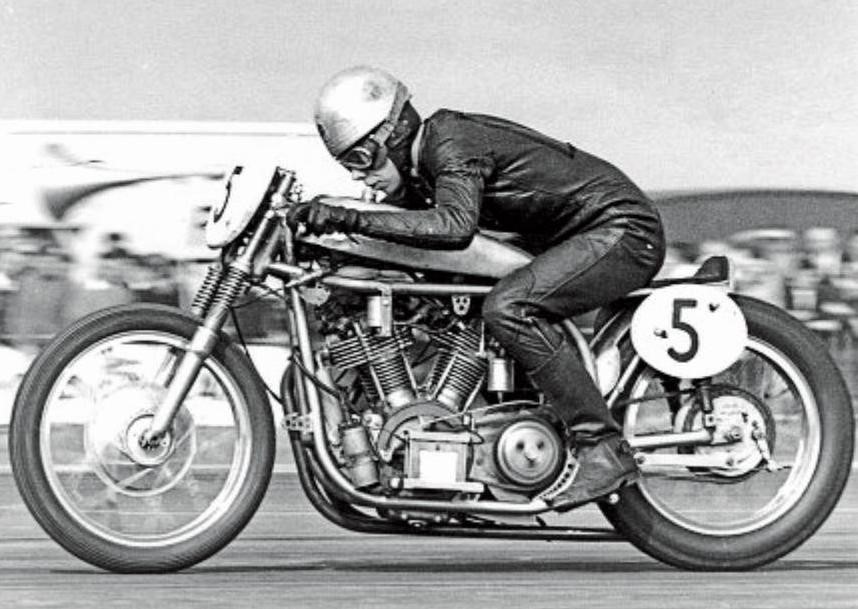

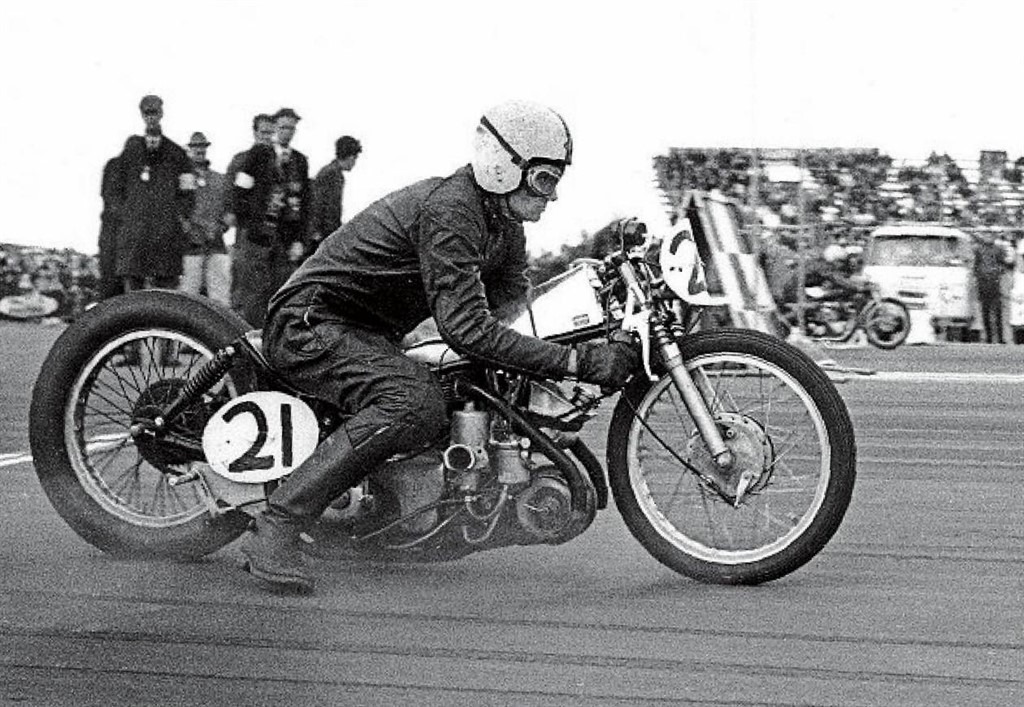

The handful of pioneering British dragsters were supplemented by a disparate mix of racing, sports, and saloon vehicles. The world of motorcycling sprinting was well established and provided a strong entry, an initial nucleus of 17 riders, with some substitution later. The competition classes were for: Up to 500cc, 501-750cc and 751-1500cc capacities. Chief among them was George Brown on ‘Super Nero,’ his supercharged Vincent. Undoubtedly the fastest of the British riders, he was close to the record-breakers’ dream of recording 200mph on British soil. There were also potential Vincent-mounted challengers, the experienced Neville Higgins on ‘Jindivik’ and rapidly rising star Ian Ashwell on ‘Satan.’

|

|

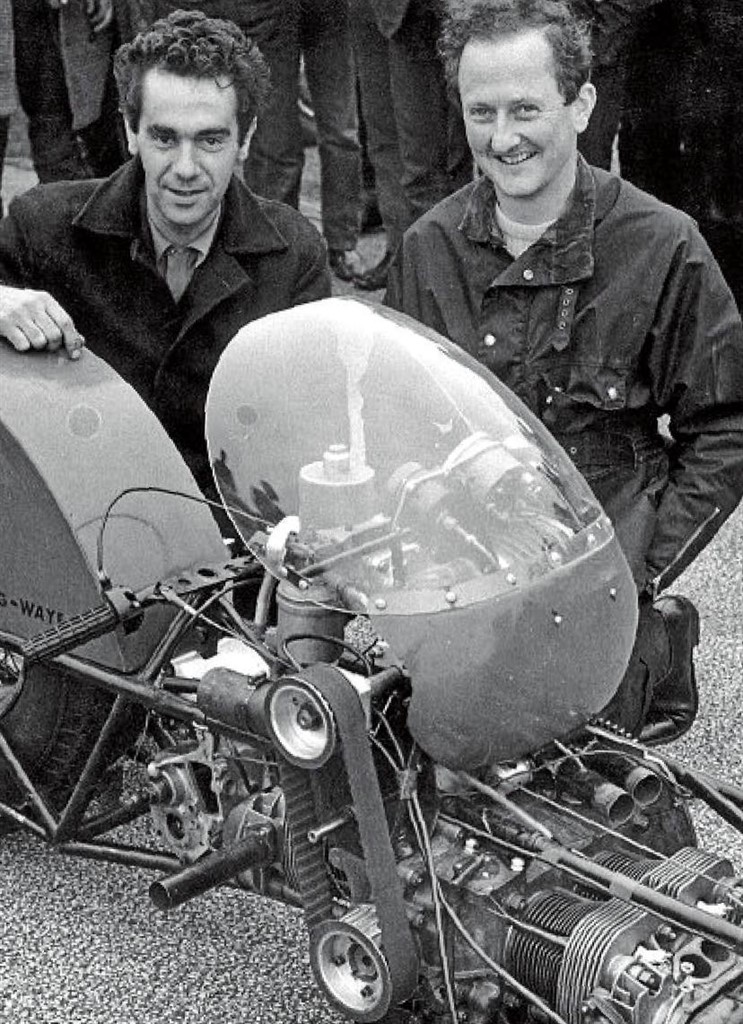

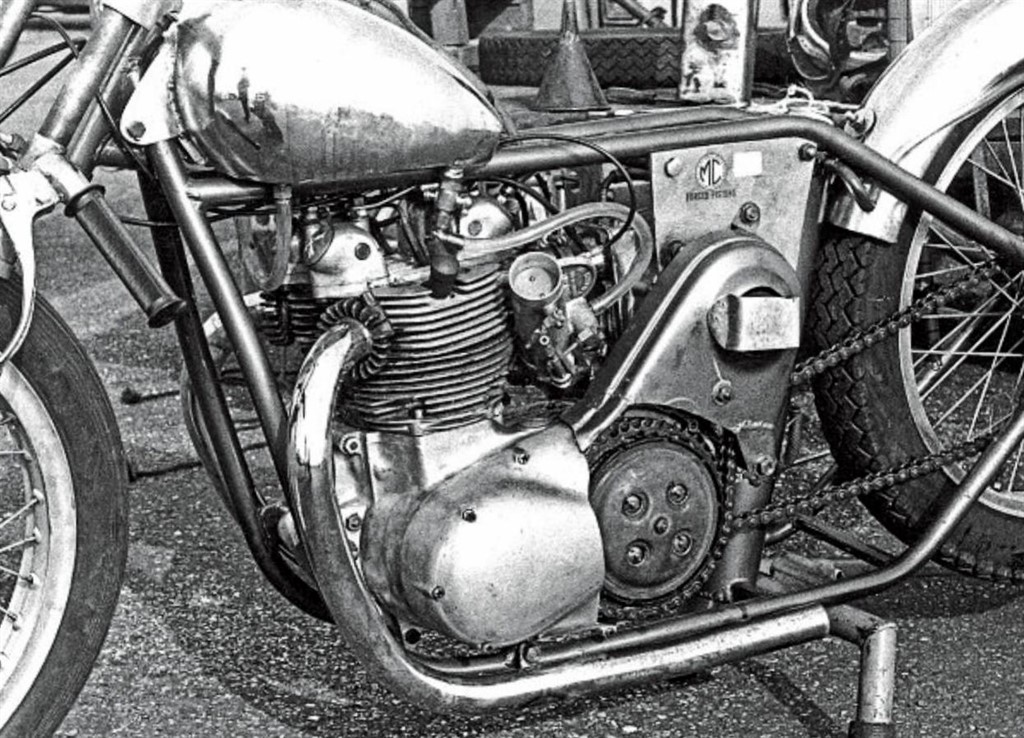

Two among the other British machines showed much inspiration from American practices. Alf Hagon had successfully sprinted a Triumph in a frame of his own building. Combining the knowledge thus gained with the principles followed by the quickest four-wheel dragsters, he was ready for his next project. Every effort was made to save weight, which is why he chose the V-twin JAP engine, inherently light compared to the Vincent alternative.

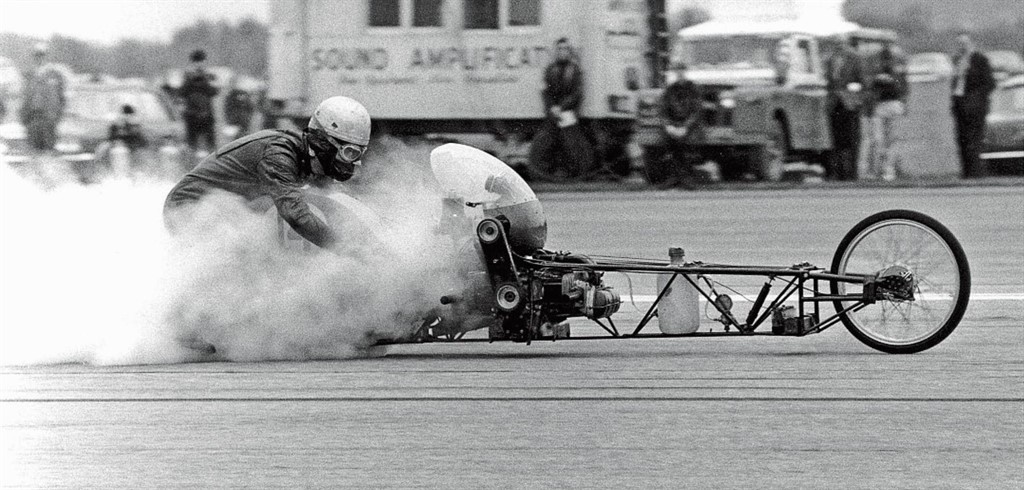

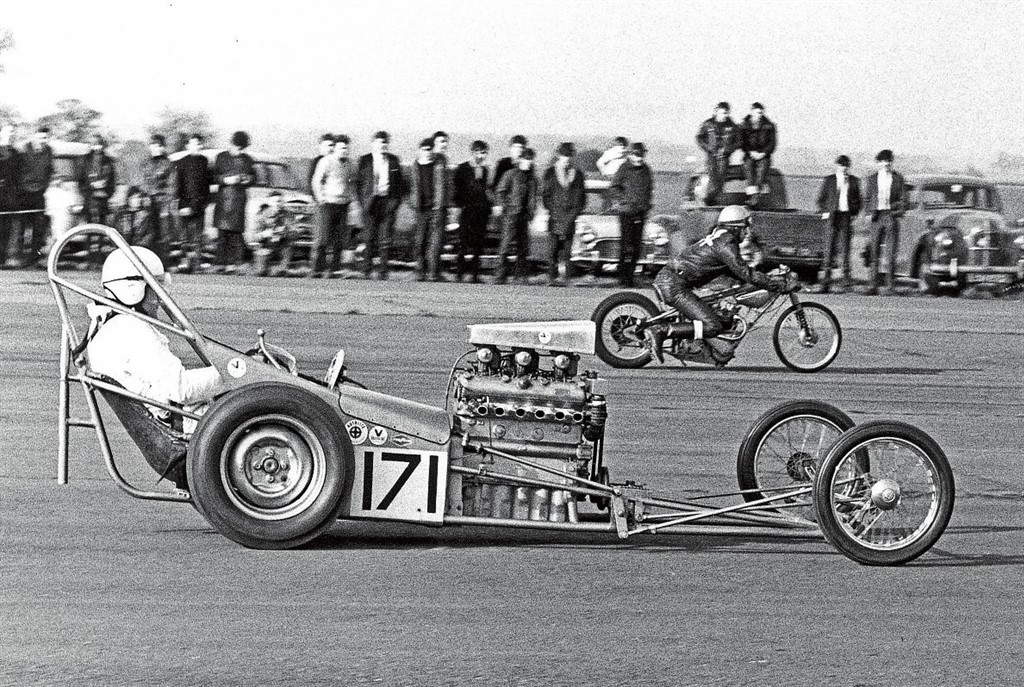

Most radical was surely Clive Waye’s ‘Drag-Waye.’ A long wheelbase, ladder-type frame seated the rider behind the rear wheel. Essentially, it was half a four-wheel ‘slingshot’ dragster. Powered by a Volkswagen engine and piloted by Howard German, the ever-improving results were endorsing the logic. The device only stabilised once it really got going and it was costing the rider dear in worn out boots. Unfortunately, it became a late arrival to the party. Further tuning and pre-event testing had resulted in a massive blow-up. The rebuild kept Drag-Waye absent from the first three meetings.

Ernie Woods was also using V-twin JAP power. He hoped to add to the illustrious history of his Manx-framed bike gained at the hands of its builder, Francis Williams. When Denis Jenkinson was not reporting on car Grands Prix, he would often sprint or hill climb his own bike, a TriBSA. In addition to his support for the Allard effort, he was happy to be a member of the motorcycle party.

|

|

The first meeting took place at Blackbushe, near Camberley in Surrey, on September 19, 1964. The jungle telegraph and pre-event publicity had worked – and how! The adjoining A30 road was blocked as more than 20,000 formed long queues. While the format had British racers competing against each other, cars v cars and bikes v bikes, they were really the warm-up act. The American racers, also competing among themselves, were the main attraction.

Nevertheless, the bikes provided some keen competition. The 500s were topped by Jack Terry, with a 12.03 best, away in front of the other seasoned sprinters, Eamon Hurley’s Manx Dragster (a sprint bike, despite the name) and Dave Lecoq’s 7R Special. Competitive in sprinting’s 350cc capacity, here they were both giving away 150cc. Steve Woods was entered on a 500cc JAP, but his was one of the extremely rare V-twin engines. Hurley recalled finding grip on one launch that resulted in a spectacular wheelie. This was described by the laconic American commentator as ‘an entry in the unicycle class.’

Pete Smith’s Hagon-Triumph was the bike on which Alf Hagon had already had success. Smith posted 11.80 as the best of the 750s after Geoff Howgego’s challenge faded. Bill Bragg and his assorted colours of ‘Perils’ had a stout reputation as a leading sprinter. He had entered on Blue Peril but suffered some expensive problems, including a destroyed engine.

The quickest of the bikes was George Brown, posting 11.25/136mph as his best of just two runs in a troubled day for the Vincent man. He only just got the better of visitor Don Hyland, who ran 11.34/128mph, apparently a way short of his best. He had bought ‘Parasite’ after it had already enjoyed a very effective race career in America. Ian Ashwell was not far behind, with another four riders in the 11-second zone. These times were better than the British car entry, but what of the stars of the show?

Drag racing at this level had been seen only in magazines, in spite of being static and silent it looked colourful and spectacular. Racers from the British side watched as keenly as the spectators. As well as the bold paint finishes, the vehicles were liberally decorated with sponsor decals. This ran counter to RAC/ACU rules, so British team organiser Len Cole had the foresight to negotiate dispensation. It was fair, as the visit would have been impossible without the sponsors’ considerable financial contribution.

The initial fire-up was relatively mild on noise, the uneven thudding stutter of a fuel engine was loud and unusual but put no one’s ears at risk. The starts were controlled by George Wells, whose gymnastic displays as he raised, then lowered, the flags were yet another new phenomenon. With the signal to go the top dragsters let rip and the noise hit home like a thunderbolt. The start area vanished in clouds of smoke delivering the acrid tang of tyre rubber and nitro that billowed after the dragsters down the full quarter mile. As the smoke cleared, there was a shocked silence, almost none of those witnessing had had this experience before.

|

|

As the watchers’ assaulted senses recovered, there was a gasp as the times were announced–Don Garlits ran 8.28/191mph to Tommy Ivo’s losing 8.46/184. A round of applause followed. Those colossal speeds achieved in just a quarter mile. Engines producing close to 1000 horsepower? It all but beggared belief! Further runs were made, but that initial shock reaction became a set pattern for the following events.

After a full day of racing, the performing circus was packing up to travel a couple of hours north to Chelveston, near Wellingborough, Northants, where the long runway remained in good condition. Next day, another huge crowd arrived but the event was troubled by a crosswind that tempered performances. Once again, riders posted times in the 11-second zone, but Higgins’ 11.11 was the best of the bikes, with Hyland runner-up again, less than 1/10th of a second shy. Eamon Hurley remembers the American team’s bonhomie was thoroughly tested at this event when Dante Duce, the team’s manager, was piloting Tony Nancy’s beautifully prepared dragster. He got out of shape, hit the finish line timing equipment, and crashed, totally destroying the car but managing to climb, unhurt, from the wreckage.

|

|

The British were learning much about engines and racing from the Americans, while they, in turn, were curious about some of the more radical British machinery. With a week’s break the British contestants went back to home and workshop. Everyone was on some sort of learning curve although the American racers were, apparently, deeply immersing themselves in British (and European) ‘popular culture.’ Read into that what you will!

The following weekend was the northern swing of the action. Saturday’s event (September 26) took place at RAF Woodvale, just south of Liverpool. The track proved challenging for the car entry, but it certainly suited the bikes and obviously Hagon. His sharp 10.71 performance beat Higgins, the only other 10-second runner with 10.88. Brown was beset with mechanical woes and his times were really a token effort. He was back in his stride the following day at Church Fenton, near Tadcaster in Yorkshire, topping the timing sheets with 10.72. Finally patched up, the Drag-Waye team and its radical offering became the focus of the American’s attention. For reliability, Clive Waye had softened the motor, but with Howard German in the back seat riding position it was still good enough for sixth fastest at 11.64. While waiting for Dragwaye’s repair Howard had been following the circus anyway, his long friendship with Dave Lecoq extended to Dave sleeping under the awning of Howard’s van. With traditionalist Terry choosing to contest the Sunbeam MCC’s Ramsgate sprint, Hurley claimed the 500 class on both days, beating Lecoq at Woodvale and Steve Woods at Church Fenton.

On October 3, the following Saturday, and the final weekend, started at RAF Kemble, between Cirencester and Stroud, Gloucestershire. Terry was back again – and how! After two 12.15 second runs he finally broke the 12 second barrier by coaxing 11.98/109mph from his 500cc JAP, a class record. Bragg’s ‘Blue Peril’ had also wrecked a gearbox to add to the earlier blown engine among a catalogue of mechanical woes. Elsewhere, Kemble produced some favourable results. In the 1500cc Class, Brown had it sewn up with a respectable 10.30/146mph. Hagon, Higgins and Hyland were also in the 10-second zone as his nearest pursuers.

On to the grand finale the next day, some 70 miles east and a triumphant return to Blackbushe. This time the crowd was even greater, reported as 30,000. Many were back for a repeat dose, others wanted to see this phenomenon for themselves. Learning quickly, the organisers had rung the changes and organised car versus bike races as well as transatlantic challenges. After riding the TriBSA in the motorcycle class, the energetic Jenks then raced Gerry Belton’s Allard dragster in the car classes.

Terry proved his first dip into the 11s was no fluke by reeling off three 11 second performances. Hurley’s 350cc Manx-powered bike ran its quickest ever by posting 12.72/105mph, first time he had run below the 13 second mark. Geoff Garside made his Blackbushe debut as he had missed the first visit. His bike was a combination of BSA A10 and A65 engine parts for 742cc with generous helpings of fuel/air courtesy of a Shorrocks supercharger. A class win at Church Fenton had foiled Pete Smith’s Hagon-Triumph clean sweep.

|

|

The NSA’s forte was timing the events as the organisation had the most sophisticated set-up. Anthony Bayley was a timekeeper, often part of the NSA team that operated the equipment. He explained that having timed the last runs of the day, everything had to be carefully packed away and taken to the next event. It was a tough schedule. For the organisers, the logistics were another problem, as there were few motorways at the time. Everyone was booked into hotels, but this became another issue. One memory is of a hotel on the tour that was not good at early Sundays and Anthony and his wife were obliged to climb out of a window to get to the track and set up the equipment.

|

|

A couple of days after racing was over, there was a grand prizegiving in London. The 1964 British International Drag Festival was intended to sell drag racing to a British public that had little idea of the concept. While cherry-picking highlights of a typical American-style meeting, it had become a convincing demonstration of the high-powered sport. Spectators were treated to the spectacle of full-on, side-by-side racing, producing times, speeds, smoke, and noise almost beyond belief. By comparison, the bike entry may have been a side show, but they could hold their respective heads high, nearly every session seemed to run on a par with the admittedly thin, American bike entry.

It was far from perfect, but no one had organised anything on this scale before. In the face of their intense schedule, the Americans were not leaning too hard on their machinery but had been determined to put on a good show. The highly tuned engines still demanded regular attention. Mechanical attrition became a problem among the British entry. There were some long gaps between races. The organisers soon learned to be prepared when engines were running nitro – the expensive, explosive but power-giving nitromethane fuel. As soon as they were fired up, they needed the bare minimum of time to warm up and come to the line.

There had been a free exchange of information between the racers concerning mechanical matters and race technique. In sprinting, the green start light meant ‘course clear,’ timing did not start until the bike, or car, moved. In drag racing it was the start of the race! The term ‘hole-shot’ had now entered the UK English lexicon. The puzzling disparity between British and American times was explained by the difference between the wartime runways used by the British and the dedicated American drag strips, carefully levelled and surfaced in a way to offer far superior levels of grip. The present British formula for success usually involved a car-type SU carburettor feeding straight methanol into a supercharged engine. The Americans ran injection systems feeding high loads of nitro.

In this country, the apparently unpredictable results using nitro fuel had generated a nervous mystique. Alf Hagon was introduced to Don Garlits, the Florida-based top American car racer and tuner. From the bore and stroke dimensions of the engine, Garlits provided a base tune for running nitro in Alf’s JAP engine. Eamon Hurley was another who remembers being convinced to the point of buying a gallon of nitro in London on his way home from a meeting. The initial excitement was soon tempered on the long-haul home as they realised, they were driving with a potential gallon of high explosive for company! He also recalls the largesse of the American sponsors. Oil and NGK spark plugs, as well as the STP oil additive were supplied readily. The red oval stickers became a ‘street cred’ add-on. Far more stickers than tins of oil additive were sold.

|

|

Behind the scenes there had been some occasions when the ascent of the learning curve was near vertical. Right at the start, the Americans were relieved when they could finally alight from the ocean liner, the USS United States, that had provided them with a storm-blighted Atlantic crossing. Race machinery, spares and tools had been brought in on enormous trailers. These were more than a match for regular British tow-cars. Army-surplus trucks had to be hurriedly bought, modified, and made compatible with transatlantic towing standards.

Many who had witnessed Dragfest were inspired to build their own cars or bikes and compete. Compared to the exotic American four-wheelers and their big V-eights, most of the British sprint bike entries were based on types of spectators might have ridden to the meeting. In those pre-classic days, older pre-unit BSAs and Triumphs, even obsolete Vincents, could be bought for £30-£50. Many effective sprinters were created from vintage bikes, which could be had for a few pounds. Sprint meetings took place all around the country. Meanwhile, seemingly on a roll, the BDRA looked to repeat the exercise the following year. With a far more focused idea of procedure and in view of the 1964 attendance it looked to be a surefire winner.